“Spending your life staring through a microscope, obsessing over tiny features on tiny things that no one cares about but you.” If you think this is the life of a taxonomist, you’re not entirely wrong – but you’re overlooking a key truth. Without taxonomists we wouldn’t have labels for species or a common language to talk about the life around us; life which can be as commonplace as our pets or the vegetables in the grocery store, or as awe-inspiring as the dinosaurs which once roamed Alberta.

The reality is this: taxonomy is about removing the blinkers. Blinkers that blind us to the fireworks of life happening all around us. It’s about searching for treasure and realizing it’s everywhere if we just learn to look for it. And like any treasure hunt, it’s filled with digging up seemingly mundane minutia requiring great perseverance and attention to detail – but the reward…well, ask any treasure hunter if it’s worth it and watch their eyes light up in the memory of a great discovery.

In taxonomy, the promise of treasure is everywhere, and the more obscure the taxon[1], the greater the promise. I have the privilege of studying lichen taxonomy, organisms which defy definition. In simple terms, lichens are a partnership between algae and fungi. Lichens have been named and described for hundreds of years, yet, to state the scientific party line – we still have so much to learn.

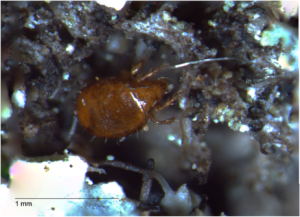

Here in Alberta, through our work with the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, we’re learning new things about lichens in our province with every sample we identify. We’re learning where they live, and how vulnerable they are to our activities. By naming a sample of lichen, we can put its life into context – where else in the world does the species live and how is it faring in other areas of its range? And by extension, we’re learning about the species that rely on lichens; species which can be as tiny as an eight-legged mite that takes shelter under a lichen lobe, or as iconic as the caribou which survive winter by the grace of lichen.

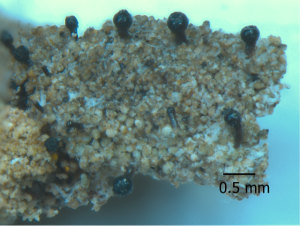

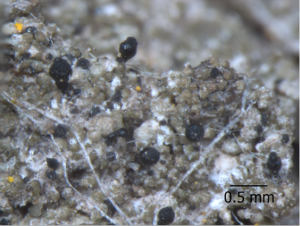

Some of the treasures we’ve found include a tiny species that goes by the scientific name Sphinctrina anglica. This black stubble-like species was first found in Alberta 43 years ago, not far from Edmonton. No additional specimens had been recorded since this first sighting…until just last year. Discovery of a new population inspired us to set out on a focused hunt. The bounty included the discovery of a third population as well as confirming its presence in the forest in which it was originally found. It’s thrilling to see this species persevering!

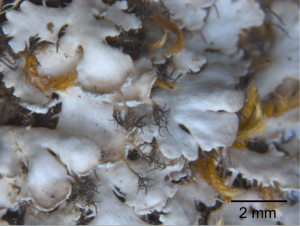

Other discoveries are a matter of re-reading the evidence. The lichen we commonly call the “Milky-skinned Centipede Lichen” was hidden in our museums for many decades, misidentified and masquerading as other species. Additional specimens and recent taxonomic work from eastern North America allowed us to flush it out and give it the recognition it deserves: an uncommon species that loves to hang out on mature deciduous trees in Alberta’s boreal forests.

These are but two stories of possibly dozens we could talk about. The same is true for my colleagues, an inspiring group of scientists passionate about their respective taxa, ranging from mites to moss, snails to shrubs. I, like them, am thrilled to be wide-eyed in nature. My gaze is increasingly unfettered to the mystery and magnificence of lichen. My hikes are slower in pace but I’m more entranced by the places I see. And if lichens don’t grab your imagination – there are millions of other species to fascinate you. Beetles, bugs, trees or toads – learn them and love them – it’s your nature to know.

Images and text by Diane Haughland unless otherwise indicated; images © Royal Alberta Museum unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Any group or rank in a biological classification into which related organisms are classified.