Old Man’s Beard (Usnea spp.)(c) Diane L. Haughland, Royal Alberta Museum

A great place to start looking at lichens in Alberta is in Crimson Lake Provincial Park located just northwest of Rocky Mountain House. Here, you can walk through a few different forest types in the course of a 10 km hike. You’ll find burnt stumps covered in baby Cladonia lichens and Cockleshell lichens. Veteran poplar trees harbour the sensitive Lung lichen and tiny black Vinyl lichens on their bases, nestled in moss. You can enter fens and bogs, with Larch and Black Spruce trees festooned with Old Man’s Beard and Horsehair lichen that look like Christmas tinsel. You might even notice the fresh, mushroom-type scent the moist foliose lichens tend to have. Once you’ve found these lichens, lean in and take an even closer look. You’ll find that lichens are home to a multitude of other organisms. “When you lift a lobe of lichen up off of a twig, it’s like taking a look under the tent of the circus bigtop,” explains Diane Haughland, a lichenologist at the Royal Alberta Museum and the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI). “You often find beautiful and bizarre mites sheltering between the lichens’ root-like growths (rhizines).”

Lung Lichen (Lobaria pulmonaria) (c) Diane L. Haughland

Lichen Super Powers: Diversity & Resilience

Lichens themselves vary tremendously in form – some look like leaves, some like little shrubs, and others look like miniature wine glasses! And with a wide-variety of fantastical names like Fairy Puke, Powdered Sunshine and British Soldiers, it’s easy to understand how lichens capture the imagination.

Fairy Puke (Icmadophila ericetorum) (c) Diane L. Haughland

British Soldiers (Cladonia cristatella) (c) Diane L. Haughland

Wolf Lichen (Letharia vulpina) (c) Diane L. Haughland

Lichens growing on a rock in Jasper, Alberta (Grey Rosette lichens (Physica sp.) and Orange lichens (Xanthoria elegans)

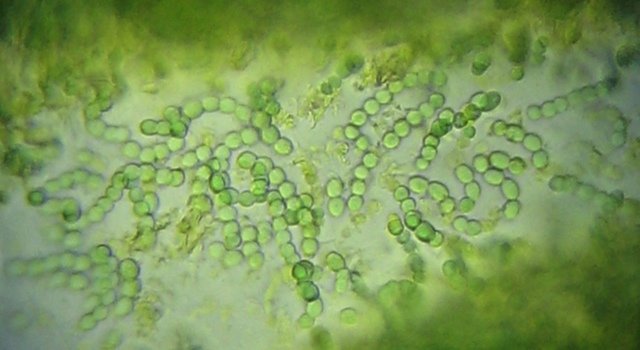

Even microscopically, the texture and beauty of the miniature world of lichens is apparent, explains Haughland. Examples include, “the soft cobweb-like surface of Dog Pelts; the fluffy, specialized fragments of fungus and algae that can disperse and grow into new lichen lining the margins of Powdered Sunshine; the gorgeous green globes of Trebouxia algae; and, the elegant chains of Nostoc cyanobacteria. Even the fungal threads of Centipede lichens have a subtle texture best appreciated, at least initially, with a microscope.”

The great diversity in lichen form and structure is likely due to their diverse evolutionary histories. The lichen lifestyle–that of a fungus and an algae or bacterium living in partnership, has evolved multiple times in very different groups of fungi. The phenomenon of unrelated families of organisms arriving at similar biological solutions to a given biological problem, such as the need for sunlight, nutrients or water, is called convergence. In many cases lichens look strikingly different from each other; but, there are also instances of lichen that seem identical in outward appearance and have a similar physiology, although they’ve evolved in different geographic regions and are in fact two different species.(1)

In addition to their diversity, lichens are so resilient to extreme environmental conditions— they can survive in hot, harsh deserts and in cold, arctic climates. “We know that lichens can exist in suspended animation for long periods – they can sequester air in their cells and maintain their shape,” explains Haughland. “They produce chemicals that protects them from high light levels that otherwise might kill the algae. They reanimate quickly– for example, some lichens can absorb dew as the sun sets and then photosynthesize during sunrise, but before the temperature rises enough to dehydrate them again. Lichens can even exist completely within the upper layers of rock, between the crystals in the first few millimetres of the rock’s surface.”

Nostoc cyanobacteria inside a Tarpaper lichen (Collema sp.), 1000x magnification (c) Diane L. Haughland, Royal Alberta Museum

Lichens in Alberta & Canada

In Alberta, each natural region -prairie, mountain, foothills, boreal, parkland and shield -contribute unique species to our lichen flora. “In ABMI’s biodiversity surveys in the forested regions of Alberta we find about 40 species of lichens on average, and that number can be almost twice as high at the most diverse sites,” explains Haughland. “That’s almost twice as many bird species, three times as many soil mite species and close to the number of vascular plants recorded at those sites. And we’re only looking at the macrolichens right now, not the tiny species of crust or dust-like lichens.”

Although Alberta is not as diverse as areas like British Columbia with interior and coastal rain forests, the knowledge gained here is relevant to many countries in the northern hemisphere because many lichen species are very widely distributed “We know of more than 900 species of lichen in Alberta at present, says Haughland, “and that number is certain to grow as we increase our knowledge of this flora.”

Lichen and moss carpeting a rocky bluff (c) Diane L. Haughland

Lichen communities are also affected by changes in their environment. For example, forestry changes the age structure and composition of forests, and this can change the substrates, moisture and light available to lichens. Because lichens typically grow slowly, they can be slow to recover. However, their slow development also has benefits, as lichens can be used to date archaeological sites, earthquake slips and glacial debris when radiocarbon dating can’t be used because wood and all other forms of carbon have rotted away.(2)

In Canada, a few lichens have been included in the Species at Risk Act. Two species of lichens are on the Endangered Species list (Boreal Felt lichen and the Seaside Centipede lichen and a few more have reached the Threatened and Of Special Concern status. For more information on these species please see www.speciesatrisk.ca and Parks Canada.

Lichens in Your Backyard

Despite her dedication to lichenology, Haughland doesn’t feel it’s her place to shout for people to pay attention to lichens – because, she says, lichens so clearly speak for themselves. “I don’t expect everyone to be intrigued with lichens – but the further down you get into the rabbit hole that is the lichen symbiosis the less likely I think you are to turn around.” Perhaps the best way to get to know the nature of lichens, she suggests, is to pick up the occasional fallen branch and get to know its inhabitants, buy or borrow a field guide, put a branch of lichen in your window or simply take a walk in your own backyard.

___________________________________________________