March 19 is Taxonomist Appreciation Day. Unsung and often misunderstood, taxonomists work in the scientific shadows yet perform research that’s critical to the monitoring and effective management of biodiversity. In this post, we hope to convince you that taxonomists not only deserve a day of appreciation, but are absolutely essential to understanding our natural world.

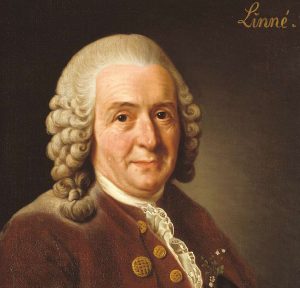

It’s true: The word “taxonomy” might not immediately bring to mind images of science at the cutting edge. Most definitions speak of grouping, arranging, classifying**—clerical busywork one is thankful is being done, provided it’s being done by someone else. Even for the biologically inclined, taxonomy begins and likely ends with Carl Linnaeus, creator of the binomial Latin naming scheme still used today and a man so thoroughly predestined to be a taxonomist that his family renamed itself after a tree. From Homo sapiens to Alces alces, we experience taxonomy through the lens of Linnaeus’ 300-year-old legacy. And for many of us, that’s where our understanding stops—things have names, which is great, but what more is there to know?

Even with the advancements of modern science, a taxonomist remains the best tool for uncovering biological meaning.

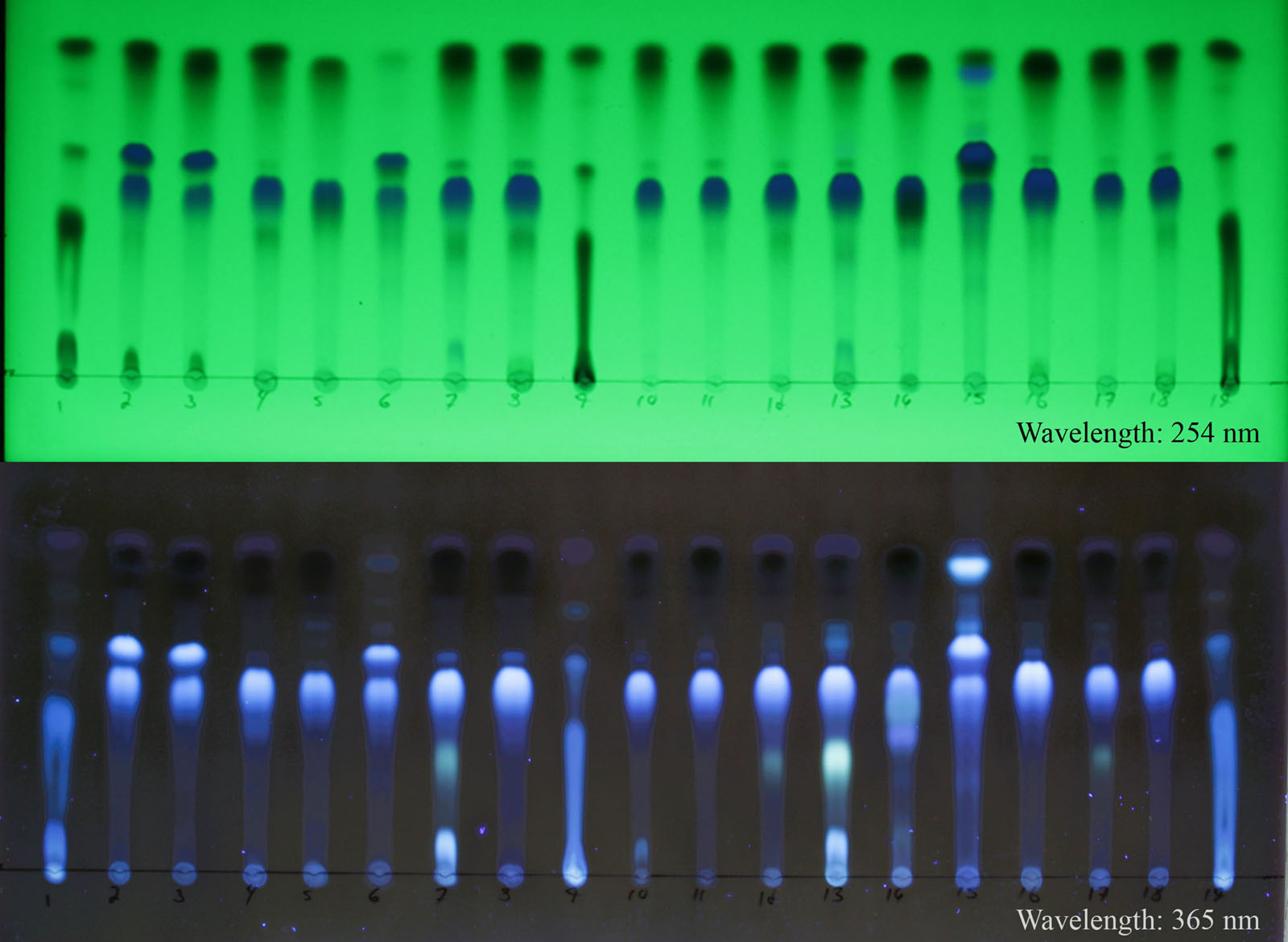

In fact, taxonomy is more relevant and dynamic today than ever, as taxonomists marry classical techniques and training with modern technology to continuously advance their science. We at the ABMI are privileged to experience this first-hand thanks to the amazing taxonomists of our Processing Centre. Working with plants, lichens, moss, mites, and aquatic invertebrates, their expertise is a cornerstone of our program. Over the years, the taxonomic team has discovered dozens of species new to Alberta or to science and collaborated with researchers from across the globe on major initiatives, from the Almanac of Alberta Acari to the Cyanolichen Network Project. Last year alone they hand-sorted, examined, and archived more than 70,000 specimens in their efforts to identify field samples and ensure ABMI data is as accurate as possible. And the work is never done: New discoveries prompt the relationships among species to be reimagined, while new tools and techniques make it possible to see and discover things that had long been out of reach.

Despite daily proof of the value and dynamism of taxonomic research, broader interest is limited. This puts taxonomists in a catch-22. On one hand, taxonomy faces the same kind of pigeonholing professionally as it does in the popular sphere: Discovering and describing species is old science, and old science is (unfairly) dismissed as uncool science, so taxonomy tends to be undervalued and underfunded. This has been called the scientific dilemma. On the other hand, and rather predictably, there’s now a critical shortage of taxonomists around the world despite the ever-increasing need for taxonomic information to responsibly manage, conserve, and use biodiversity. This has been called the taxonomic impediment. At the ABMI we like to say that you manage what you measure. Without taxonomy and taxonomists, we wouldn’t know what we were measuring, and therefore what might need to be managed, in the first place. The same is true around the world.

Meanwhile, the bias toward novelty and the need for more taxonomists has spurred the adoption of cutting-edge techniques that promise more resolution in less time. From DNA barcoding to AI-assisted species recognition tools, these advances can bring incredible new clarity and insight (we proudly incorporate many such techniques at the ABMI). But despite their many benefits, they can also play into the stereotype—a new kind of “impediment”—that taxonomy itself is outdated, that without these advances it has little to offer, and that taxonomists are antiquated and unnecessary in an automated world where the tools become substitutes for the people who use them. Nothing could be further from the truth.

While modern techniques have increased taxonomists’ ability to “see” in amazing ways and deserve their rising status within the toolbox of integrative taxonomy, the traditional craft of the taxonomist remains crucially important. DNA is a powerful tool for identification and differentiation, yet species are more than their DNA. Photographs convey fine detail and are easy to store, yet can’t be analyzed, manipulated, interacted with, or experienced with the same nuance as physical reference specimens. Neatly classified taxonomic groups aren’t static end-products; they’re living hypotheses about the evolutionary relationships among organisms. One essay put it this way:

A substantial contribution from taxonomy to science and society in general will not come from huge numbers of species names destitute of biological meaning, but rather from reliable evolutionary hypotheses regarding natural entities—the expected outcome of thorough research by professional systematists.

Even with the advancements and conveniences of modern science, a taxonomist remains the best tool we know for uncovering that biological meaning—for finding order amid chaos and making sense of our living world. Far from being replaced by new technology, today’s taxonomist has embraced it to be more creative and effective than ever.

So join us in raising a glass to the taxonomists of the world, at the ABMI and beyond. From its roots in Linnaeus’ garden, their work has grown with the times while staying true to a tested formula of patience, observation, and informed insight that’s as relevant and vital today as it was 300 years ago.

**Taxonomy humour: Taxonomy is the study of organisms and how you phylum.