Gathering reliable measurements of animal populations is a long-standing challenge for wildlife biologists around the world. Estimating population size and density requires researchers to count individual specimens; this is an especially difficult task when working with species that move (sometimes over large geographic ranges) or live in difficult-to-traverse landscapes, like Alberta’s Rocky Mountains or its boreal forest.

Traditionally, animal data has been collected using visual and audio observations, in addition to using indirect signs of animal presence, such as tracks, hair samples or scat. However, technological advances and the increasing availability of motion-sensitive camera traps have scientists cautiously optimistic about the potential impact of new research methodologies on the field.

Above: ABMI camera trap photos (1) A Black Bear and her cub in the boreal forest; (2) A Cougar at night; (3) A Pronghorn Antelope in the grasslands

Above: ABMI camera trap photos (1) A Black Bear and her cub in the boreal forest; (2) A Cougar at night; (3) A Pronghorn Antelope in the grasslands

Since the late 1800’s, researchers, hunters, naturalists and photographers around the world have used automatically-triggered cameras to capture animal photos. Over the last 20 years, more modern infrared camera traps, also known as wildlife or game cameras, have been widely used (check out Smithsonian WILD for over 206,000 examples!) The small, battery-powered units are designed to take photos when triggered by movement, such as a Pronghorn bounding through the grassland or a Great Horned Owl swooping through the trees. Along with the image, additional information such as date, time, and temperature may also be stored on the unit’s memory card.

The use of camera traps allows researchers to “keep an eye” on study locations without having to be physically present. The benefit? More data can be collected over a larger geographic range, and for a longer period of time. As a result, the ABMI recently considered adopting camera-based protocols to monitor mammal populations instead of using winter tracking protocols. Winter tracking—based on finding and identifying animal tracks in fresh snow—is both logistically difficult to execute, as well as time consuming.

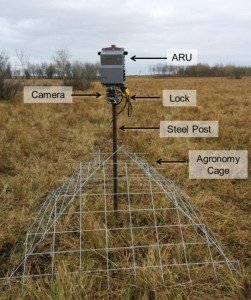

After several pilot projects, the ABMI’s Monitoring and Science Centres established new camera-based mammal survey protocols—currently being implemented for the 2015 field season—including, the deployment of four motion-sensitive cameras at each terrestrial site (along with sound recording Automated Recording Units, or ARUs). This past February and March, field coordinators and technicians visited sites to set-up cameras on trees and posts, a change from their previous routine of traversing 10 km transects looking for animal tracks in the snow. The cameras will remain operational in the field until they are collected again in July.

The ABMI’s new monitoring equipment (ARUs and camera traps) are protected with agronomy cage in pastures.

The switch to camera trapping to monitor mammal populations was a big decision for the ABMI. New equipment had to be purchased. Monitoring plans had to be adjusted to accommodate the new methodology. The ABMI, however, is always looking to innovate how it collects biodiversity data to fulfill its mission more effectively—“to track changes in Alberta’s wildlife and their habitats from border to border, and provide ongoing, relevant, scientifically credible information on Alberta’s living resources.” Adopting new technology and methodologies does have its challenges, though.

A recent review of wildlife camera trapping studies in the Journal of Applied Ecology (written by ABMI collaborators at the University of Alberta, Alberta Innovates Technology Futures, University of Victoria and University of Montana), suggests that while there is great potential for effective ecological inquiry and biodiversity monitoring using camera traps, more explicit consideration of underlying animal behaviour and thorough reporting of methodologies is needed.

Camera traps are attached to posts using a special bracket to angle the lens towards the ground.

For example, the review suggests researchers must learn how to effectively measure and report the probability of an animal being detected by a camera, manage sampling design (e.g., distribution and number of cameras) to contend with spatial variability, as well as determine how to tell individual animals apart that do not bare unique patterns (like those worn by Leopards or Zebras).

Of course, there are also new logistical issues in the field that must be contended with. For the ABMI, these hurdles have included learning how to access sites in the winter, protect equipment from vandalism (by both humans and animals), and prevent damage by farm equipment and cattle. Standardizing deployment protocols has also challenging, given the diverse landscapes and habitat types that the ABMI surveys. For example, how do you make sure the camera is angled at the ground in the exact same way at every site? A custom-built bracket, of course!

A Black Bear chewing on a camera trap lock in the remote boreal forest, captured on photo!

The ABMI is making every effort to ensure transparency in our research by publishing our protocols on our website (camera/ARU deployment protocols to be released), and actively engaging in scientific research using camera traps. By continuing to work collaboratively with wildlife biologists, the ABMI hopes to assist with the development and implementation of more effective monitoring of Alberta’s wildlife populations.

Follow the ABMI on Facebook or Twitter to see more camera trap photos #CameraTrapTuesday.