Working for the ABMI as field technicians, crews of young scientists experience Alberta’s great landscape, hoping to unearth even its tiniest treasures. Some of its larger treasures, they found, are black and furry and love pasta.

Working for the ABMI as field technicians, crews of young scientists experience Alberta’s great landscape, hoping to unearth even its tiniest treasures. Some of its larger treasures, they found, are black and furry and love pasta.

Here are some of their stories.

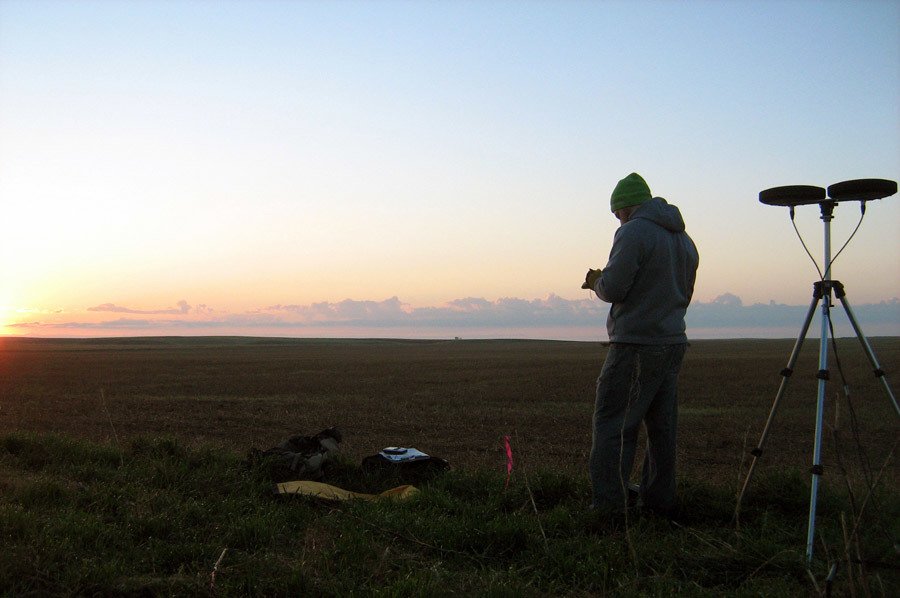

At two in the morning the damp, cool and moist air clings to skin like the breath of ghosts. Wraiths of mist gently rise up and wrap the swishing grasses, caressing leaves and stems as you make your way carefully to the site you’ll work at, preparing to record the dawn chorus of Alberta’s avian choristers. Later, you’ll carefully map and scan the earth for its treasure of lichens. Birdsong is yet to begin. The world is still.

For Leanne Marcoux, a graduate of the University of Guelph’s environmental studies program completing her second season with the ABMI, being in the pre-dawn landscape was an experience bordering on the spiritual. “You get to be in these untouched, remote landscapes,” she says. “It’s very humbling and inspiring – spiritual in a way. You’ll be sitting there and a coyote will just come right up to you to see what you’re doing. It’s amazing.”

It’s also the experience of a lifetime for many of the young men and women of the ABMI’s land crews, who answer the call to monitor the province’s biodiversity every summer. Besides marrying their love of nature and keen interest in the earth’s bounty, it’s also advancing budding careers in ecology. Monitoring crews can be stationed anywhere in the province: in the boreal in the far northeast, or deep in ranchland in southwest.

“I came from Ontario to gain Western Canada experience,” explains Marcoux, who spent the summer in Alberta’s southern grasslands. “This was the perfect opportunity for me to get hands-on learning in Alberta. I hope to expand my career in environmental consulting with this broader experience base.”

After spending three months in the field doing biodiversity surveys, the field crews return to the University of Alberta where they spend a month sorting and identifying field samples. Crews are divided into lichen, moss, and aquatic invertebrate labs.

This year, the lichen lab at the University of Alberta is teeming with activity as crew members examine their bounty of lichens under the guidance of the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute’s lichenologist, Dr. Diane Haughland, of the Royal Alberta Museum.

“The crews collect lichen samples in the field by focusing on form and habitat, but the real fun begins when they look at their samples through the dissecting scope,” explains Haughland. “Our technicians learn to identify the most common lichens and they repackage the remaining specimens for me and my team to identify during the fall and winter. That’s how we decipher the story that lichens are telling us about each site’s ecological condition.”

Chris O’Sullivan, who holds a master’s degree in molecular ecology from Queen’s University in Belfast, Ireland, found it was not only a chance to expand his international experience, but also a chance to experience Alberta’s remote northeast. Based in Fort Chipewyan, O’Sullivan says he loved the remote camps in the boreal forest. “We were flown from site to site by helicopter. That was fun and interesting. I hadn’t done that before!”

It was also the first time he’s looked for lichens and, proving that the luck of the Irish is no myth, O’Sullivan was part of a team that found one of the rarest lichens in Alberta, known as antler lichen. “It’s only been found once or twice before in the province,” says a delighted O’Sullivan, who hopes to find a position in Canada this year. “The last published record I could find for this species was from the 1980’s,” Haughland confirms.

Ryan James, a student at Lakeland College’s ecology program was surprised to find lichens in the most unusual places. “Some are only a millimeter in diameter,” he says. “You find them on twigs and even fence posts. I found these pretty cool jelly lichens. When they’re dry they look like a bit of crust on the soil. But when they’re wet, they’re like jelly – soft and squishy.”

Nils Andersen who recently completed a master’s degree in ecology at the University of Alberta, worked in Alberta’s northeast, out of Wabasca and Fort Chipewyan. Though his own research had looked at the impact of beavers on amphibians, he found looking for lichens both “challenging and satisfying,” he says. He also found that black bears are pasta lovers. “We came back to the camp and found a young black bear eating our lunches. He ate all of my pasta – but spat out every piece of yellow pepper!”

Sometimes it’s the chance to do field work for the first time that attracts. University of Guelph undergrad, Kaila Ritchie, is majoring in natural resource management. “It sounded like a lot of fun, as well as good experience,” she says. “I worked in both wetland and terrestrial sites, flying in and out by helicopter in the Wood Buffalo area. It was pretty exciting and I learned so much. I definitely want to do more.”

For Latifa Pelletier-Ahmed, a University of Calgary botany alumna, field work complemented her knowledge of plants. “Field work is an amazing way to study a lot of plants. I found that even though I had a good foundation of knowledge about plants, I hadn’t had a lot of field experience. I certainly got that. I’ve learned about hundreds of species in southern Alberta,” she says.

It’s the diversity of experience that brings science students and recent grads from across Canada and abroad to experience field work in Alberta, guided by some of the country’s top scientists. And it’s what keeps them coming back. Christine Pachkowski, a Fort McMurray native and a graduate of the University of British Columbia program in resources conservation has just completed her second season, this time working on parkland sites in southern Alberta. “I felt better prepared this year and had a better idea of what to expect,” she says. “One of our sites was in someone’s backyard. That was different. We had lots of great experiences talking to land owners – and plenty of encounters with cows!”

Interested in working on a monitoring crew for the ABMI next summer? Apply now: http://bit.ly/1apEBmL The competition closes on January 31, 2014.

How the ABMI measures biodiversity

The ABMI collects data on Alberta’s species and habitats at 1656 sites located systematically in a grid – every 20 km – across the province. At each site, data is collected from both land and water habitats. To understand trends in biodiversity, the ABMI crews revisit each site every five to seven years. Data are stored on the ABMI’s website at www.abmi.ca and are publicly available.

Feature image photo credit: Caitlin Willier